Gagosian Quarterly

John Currin speaks with Brett Littman about drawing.

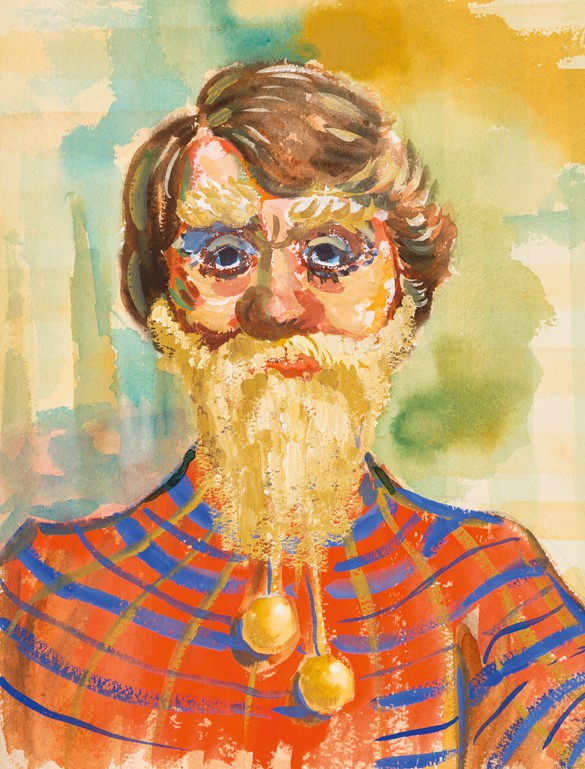

John Currin, Untitled, 1995, gouache on paper, 13 ¾ × 11 inches (34.9 × 27.9 cm)

John Currin’s ambitious paintings seduce, repel, surprise, and puzzle. His masterful technique is achieved through the scrutiny and emulation of the compositional devices, graphic rhythms, and refined surfaces of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Northern European painting, while his eroticized subjects exist at odds with the popular dialogue and politics of contemporary art.

Brett Littman is the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, Long Island City. He has contributed news and commentary to a wide range of international art publications and critical essays to many exhibition catalogues.

See all Articles

BRETT LITTMAN: John, is drawing an important aspect of your work?

JOHN CURRIN: Well, I’ve always drawn. In the past, drawing was a tool for me to procrastinate. It was a way to put off the difficulties I was having in painting. I used to buy bound sketchbooks and spend hours filling them up—mostly bullshit drawings and then occasionally something lovely.

BL Do you feel you have a lot of facility with drawing?

JC I always drew as a kid but I never really thought I had a particularly elegant or even distinctive style. Early in my career, drawing was a noncommittal way to try out different personas and styles. Paper is cheap and you can work through things without stressing out the way you do when you’re painting.

BL What were some of the personas or styles you tried out?

JC I was making funny drawings in an illustrational style—observational drawings, idea drawings, scenario drawings, drawings from stock photography. I felt very free, I could be any kind of artist I wanted to be. But as time has gone on and I’ve focused more on painting, my drawings have become a place where I work out problems in paintings.

BL So now a drawing might look like a page of studies of arms, or folds in a fabric, or eyes?

JC Here’s a book of drawings for the unfinished painting over there. In these drawings I’m thinking, Where is this thing going to go? What’s the mood? How do I use these faces from a Sears catalogue? Some of them are explorations of stylistic things, like making a shadow, or drawing someone smiling. This one shows a ring that I wanted to put in the painting, so I needed to draw it to see what it looked like.

BL You seem to have been drawing a lot recently? There are a lot of sketches here.

JC It’s embarrassing, but one of the reasons I’m drawing a lot more is because I got a new fountain pen. It’s amazingly convenient. It’s like when you get a new phone and you can’t believe it was so annoying that it took a millisecond longer to do something before on your old phone. I find not having to dip a quill into an inkpot just changed my life.

BL Beyond the convenience of the fountain pen, do you like the quality of the line you can draw with it?

JC I like fountain pens because they feel like a massive shortcut. In the past I had to use graduated ink washes to achieve what I can now do with this one tool. Since the ink is water soluble I can get it to bleed and do things quickly without having to prepare a new pot of ink or pick up another quill. Interestingly these new drawings are all ink—there’s no pencil at all, I just start and finish in ink.

BL Your drawings seem to modulate easily between clumsy and finely rendered work. What is interesting to you about those two polarities?

JC I can render well if I really try, but I’m not nearly as good as Cecily Brown, Elizabeth Peyton, Karen Kilimnik, or Neo Rauch. They all have this amazing fractal personality in every line they draw. In any case, though, I’m interested in the idea of “bad drawing.” For instance, at one time Scandinavian porn magazines that got sent to England couldn’t have photographic porn on the front covers, due to import laws, so they’d make these cheap oaktag covers to go over them, and there’s a group on pink paper with black on it and with these illustrations that to me seem to be made by someone who has never actually seen a woman naked. I’ve only found about six by this guy, who my assistant and I have nicknamed “Ramirez.” To me they look cool, and I’m fascinated by how naive this illustrator was about his subject and how that affected his drawings.

BL Well, in the late 1980s you did draw cliché things like unicorns.

JC Yes, I did. I guess I was just trying to figure out how “bad drawing” works. I can draw a terrible drawing well or a good drawing badly. This has fascinated for me for many years now and really determines how good I am or how clumsy I am in the medium.

BL How did you react to the survey of your drawings at the Gagosian booth at Frieze New York last April?

JC In the end, it was a strangely moving experience.

BL I think for a lot of people it was a revelation—a whole aspect of your work that really hasn’t been seen since the show that Jeff Fleming did of your drawings at the Des Moines Art Center in 2001.

JC That may be true. One thing that looking at all my drawings made me feel was that they’d been fun to make. A lot of them I made just to amuse myself, and that really allowed me to come up with my best ideas. I remember when I first went to art school I did four drawings of my girlfriend asleep. I remember one of them well: it had some nice delicate cross hatching and I thought it was really well done. But later I realized that I just couldn’t handle that kind of texture across the whole drawing and at some point the whole thing just collapsed. It didn’t have that Cézanne thing, his ability to recapitulate the whole image in the smallest part. His drawings are like an interconnected solid unbreakable thing.

I guess another realization I’ve had looking at these drawings is that they always have some laggard part that doesn’t work. As soon as I start over-refining my drawings they wheedle down to nothing—kind of like a Giacometti stick figure.

BL How many drawings do you think you’ve made in your career?

JC We catalogued the drawings to prepare for the Frieze booth and ended up inventorying about 6,000.

BL The group at Frieze included a couple of collaborations that you did with your wife, the artist Rachel Feinstein. Can you talk about those?

JC We sometimes do a collaborative drawing where she makes an outline and I shade it. The rule is that I’m not allowed to change her drawing. Rachel is a pretty free spirit and she’ll just make the craziest shit you’ve ever seen, like hands that are all messed up. And then I just try to make the hands look like an Ingres drawing, all perfectly toned and shaded. I love doing those drawings—it’s great to see this thing come alive with Rachel’s wit and energy and my sort of luxurious touch.

BL The drawings at Frieze included one of a black man with a baseball cap. What can you tell me about that?

JC I wanted to draw an old Southern black guy from the 1950s. I was interested in this image stylistically—it was like an old WPA photo, and I wanted to see how I could draw his features and skin tone with the minimal amount of visual information.

BL What about the drawings of young boys that you did in the early 1990s?

JC In 1992 I was doing images of boys based on some images I had seen of young nude boys with black socks on by Filippo De Pisis. I wanted to make these drawings look like German drawings from the ’30s of blonde boys running free. This drawing here of a precocious boy was a kind of experiment in this series. He has Caucasian features but I drew him with brown skin.

The idea of playing with skin tone in drawing stuck with me. In 2003, I found a lot of stock advertising images of staged interactions between white and black people. These scenarios always make a big deal of black and white people being friends with each other—they might be laughing together, or playing pranks on each other. When I drew these images in a caricatural style, they got more abrasive and uncomfortable. It was interesting to me to see how by playing with pictorial style one could change the meaning of the original image.

BL This drawing of a nude woman with an abstract head seems like a real anomaly for you. Can you tell me a more about its origin?

JC It was from a New York Times op-ed illustration. The topic of the editorial was women’s health or birth control. I used to look at those types of drawing quite a bit, I really liked their faux-naive style. In the original, the woman is clothed, so I decided to make her nude and gave her square pubic hair and square nipples. I wanted to make this drawing half Otto Müller and half Cubist, to project some sort of socialist dream.

BL There are also a lot of drawings of couples—a bearded effeminate man with a woman, for example. What were you trying to do with those drawings?

JC In 1994, I started to think about androgyny. First I made androgynous middle-aged women with closely cropped haircuts. Then I decided to split them into men and women. When I started to draw the men, I would start with a female face and then put a beard on it. So the busty women and the bearded guys become parodies of their sex.

BL The ’90s seem to have been a really prolific time for you in terms of drawing. What drove you to draw so much during that decade?

JC I was young and I had a billion ideas that I wanted to paint. I would draw them and then try and paint them. For instance, the bearded guy and the babe was a great image for me. I made several paintings of this image that I was very happy with. But my drawings of unhappy busty girls, or girls with one boob, or this one of a nude in a perspectival setting, never really worked out as paintings. I think today I have fewer new ideas since I’m not drawing as much. In the ’90s I used to draw way more than I’d paint. I was young, scared, and not committed to anything—I wanted to try things out quickly and move on. Drawing was the way I could do that.

BL A drawing of a pregnant woman with garbage in her hair from 2005 seems to bring together several ideas that you were working on at the time. Was drawing an easy way for you to combine ideas?

JC Yes. In drawing I could do things like combine unnaturally pregnant women and draw them with garbage on their heads. This image later became a print, and from that print I made a painting. If I had more time, I’d love to make more prints. They seem right now to be my preferred source material to paint from. There’s something in the process of making a plate and a print that refines and edits visual information for me in a good way before I paint.

One other thing I want to say about drawing is, it’s always been a great way for me to fix mistakes. You know my trump card is to add a beard and sunglasses when I screw up a face.

BL Have you ever worked in pastel?

JC Yes, though I think I’ve now lost the ability to work in that medium. I used to make cool pastels in art school but today I just can’t control the color and material anymore. That said, I admire Degas’s and Manet’s pastels. Degas’s are a little easier to understand because he does it in vine charcoal and then does a hatch to build up the color. Manet’s pastels are more mysterious—how did he do that by just using the side of the pastel and blending?

BL Do you think you’ll come back to making drawings on paper outside of a sketchbook again?

JC I’ve been thinking about that. It would solve some of my problems in some of these recent paintings I’m working on. Maybe I should break out the black and white chalk and the blue paper again?

BL Can you describe for me the connection between your source material, your drawings, and your paintings?

JC If I’m working from a photograph it’s always better to make a drawing from the photograph and then paint from the drawing.

BL Why is that translation important? You can’t just put the photo on the wall and start sketching that out?

JC If I took a photograph of your shirt right now, it would have too much information—things I don’t need to see to paint it. If I were to draw from this photograph I’d say to myself, “There’s just too much going on there, I can’t keep track of it, I’m not smart enough.” But if I made a drawing from the photograph, I wouldn’t draw all of the folds and I’d end up with an image infinitely more relevant to the way I paint.

BL So drawing a photograph is a way of editing out unnecessary information?

JC Well, maybe it’s a way for me to neglect things that I don’t want to deal with. Drawing a figure from a photograph is much easier than using a live model. When I draw live models, a kind of a dumb realism starts to surface and like some stupid academic artist I start to draw every muscle and toe perfectly. This kind of drawing loses all its excitement for me, and the translation of a photo to a drawing is a good way to avoid this academic tendency I have.

BL These painted Mylars of flower arrangements, vases, or colors over here on the wall—what are you doing with those?

JC I’ve been into accessorizing my paintings recently. These transparent Mylars are a kind of shortcut, maybe even a form of drawing for me: I’m putting them over the paintings to see if ideas work before actually painting them in. When I first got a computer and realized I could take a photograph of a painting and then draw on it, Photoshop it, and add stuff without fucking it up—that was a big revelation for me. But when you sit in front of a computer for hours, your eyes get screwed up, and then of course there’s the Internet, there’s porn, and all kinds of other distractions. So now, instead of going on the computer, if I want to figure out how to paint something exactly right—like the little orange tie on the neck of the woman in that painting over there—I just do it on the Mylar and put it over the painting. This way I can see exactly what’s going to happen, not the idea of what might happen. It’s a stupidly simple concept but it totally works for me.

BL John, my final question is, how do you define drawing?

JC I guess I would say I’ve always had a slightly contentious relationship to drawing. Ingres called drawing the probity of art. To me that idea is so depressing, it brings me down—I’m battling the idea that drawing is the probity of art, I think of it more as a flirtation with the real. Painting to me is like, we’re both naked in front of each other. Drawing is like, we went on a first date and if we don’t like each other one of us can just get up and leave.

Artwork © John Currin. Photos: Rob McKeever unless otherwise noted

Now available

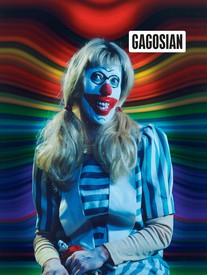

Gagosian Quarterly Spring 2020

The Spring 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #412 (2003) on its cover.

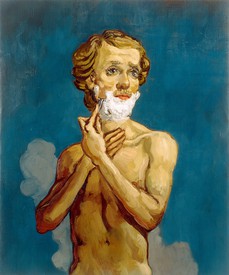

Mansplaining: Figuring Masculinity in the Age of #MeToo

In light of recent developments around the definition of masculinity in American culture, Alison M. Gingeras, the curator of John Currin: My Life as a Man at Dallas Contemporary, looks closely at the artist’s depictions of male subjects.

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2019

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

John Currin: On Drawing

John Currin on the relationship between his drawing and painting practices.

In Conversation

John Currin

The artist speaks with Derek Blasberg on Los Angeles, Kippenberger, and his newest body of work.

In Conversation

Takashi Murakami and Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist interviews the artist on the occasion of his 2012 exhibition Takashi Murakami: Flowers & Skulls at Gagosian, Hong Kong.

Jenny Saville: Painting the Self

Jenny Saville speaks with Nicholas Cullinan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, London, about her latest self-portrait, her studio practice, and the historical painters to whom she continually returns.

Pathologically Optimistic

Paul B. Preciado joins Alison M. Gingeras and Jamieson Webster for a conversation about this difficult, extraordinary moment, as part of “New Interiorities,” a supplement guest edited by Gingeras and Webster for the Winter 2020 issue of the Quarterly.

Fashion and Art: Gaia Repossi

The creative director of the Parisian jewelry house Repossi speaks with the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about her enduring love of Donald Judd, her use of photography and drawing in the design process, and the innovative collaborations, with visionaries like Rem Koolhaas and Flavin Judd, behind their retail spaces.

In Conversation

Jeff Wall and Gary Dufour

Jeff Wall speaks to Gary Dufour about his new photographs, made on the beachfront of English Bay in Vancouver, Canada, that record the endlessly varied and shifting patterns created in seaweed by the ebb and flow of the tide.

Frank Gehry Drawings

Frank Gehry speaks to Jean-Louis Cohen about the early years of his practice, including his work with LA artists, and the role of sketching in his design process. The first volume of the catalogue raisonné of the architect’s drawings, edited by Cohen, was published by Cahiers d’Art earlier this year.

Jia Aili: Before the Images Are Formed

Curator Shen Qilan speaks with the artist about his latest works.

0 thoughts to “Draw of two girls dating”