Sorry: Most popular dating app in west bank palestine

| Most popular dating app in west bank palestine | |

| Most popular dating app in west bank palestine | 342 |

| HOW SHOULD I ASK A GUY OUT ONLINE DATING | Sexy girl pictures from online dating sites |

| Most popular dating app in west bank palestine | 226 |

Most popular dating app in west bank palestine - the

Tinder as a methodological tool #EmergingDigitalPractices

Imagine being able to remotely and anonymously search through locals in your area, browse through pictures of them, and chat with those who also found you attractive. Imagine if you could use your smartphone to do this from the comfort of your own home. For those not familiar with Tinder, it’s a hugely popular dating app that allows users to swipe through seemingly endless potential partners and form matches with those who were attracted to you. Tinder functions by accessing the user’s location and showing Tinder users based on age, gender, and distance preferences from 1 to 160 kilometres away. It only allows you to be approached by people who you have chosen. As a woman, you are more or less guaranteed matches, conversation, and dates. Imagine the kind of safe, manageable contact with new people you might have. Now imagine, what this might mean for an ethnographer conducting research in a militarised war zone that is both socially and religiously conservative, divided by strict borders and with little to no contact between the divided populations.

My research looks at everyday life and the politics of space amongst Palestinians and Israeli settlers in the Occupied Palestinian West Bank. Palestinians with West Bank ID cards are forbidden to exit the West Bank without permits, which are difficult to obtain from the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF). Meanwhile Jewish Israelis are forbidden to enter areas of the West Bank designated as Area A – the largest Palestinian cities of Ramallah, Nablus, Bethlehem, Jenin, and so on. The remaining 60% of the West Bank is “shared” between Palestinian towns and villages, illegal Israeli settlers, and the IOF.

This setting offers me the unique experience of learning about two culturally different but geographically proximate groups who, despite regular outbreaks of hostility between them, have relatively little contact with each other. As an ethnographer, conducting research among both Palestinians and Israeli settlers is not an option in terms of building trusting relationships or managing my own emotions about the conflict. Movement after sundown in the West Bank is restricted to those who have cars, and the dangers of night-time IOF raids, checkpoints, and the surge of attacks on settlers have to be factored in to travelling between spaces. Safely building relationships and knowledge about members of both communities without arousing suspicion or compromising my well-being is a difficult task, not to mention building personal and even romantic relations with those around me.

Luckily Tinder is not restricted by the occupation’s enforced ethnic separation, placing Palestinians, Israelis, and IOF soldiers on a relatively equal playing field of access.

In addition, since smartphones have become more ubiquitous than personal computers in Palestinian and Israeli society, their owners have been afforded independent and private Internet use. A new kind of private communication between individuals can now occur, including romantic and sexual exchanges, occurring on such popular messaging platforms like Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, and Viber, which provides instant messaging features for known people. Conversely, Tinder opens up the potential of messaging between unknown individuals, with an explicitly romantic and/or sexual interest.

We are no longer living in the days of fieldwork as a remote exile of Malinowskian standards. While loneliness in the field may be inevitable, smartphones and social media have also changed the way we conduct fieldwork – we have to work a lot harder to distance ourselves from our friends and family if we conduct our research abroad. Once in the field, I found myself using my phone just as much as ever to keep in touch with friends and family. Having lived in London for the past few years I was accustomed to using Tinder, where it has become fairly common among single young people. Naturally I was curious about how it was being used locally and I found plenty of nearby users. I created a new profile with pictures of me in various neutral locations, removed any personal information (such as school or university that are automatically included from your Facebook profile). I also included a short introductory sentence on my profile in English explaining that I was new to the region and adjusted my settings to include male users aged 24-35 within 45 kilometres of me. While I did experiment with viewing both women and men, Tinder does not make it possible to converse with users unless they “match” you, which means that as a woman trying to talk to other women who identify as heterosexual is difficult.

With the range of distance that Tinder allows, I discovered users over Israel’s Apartheid Wall in Jerusalem (14km), Tel Aviv (45km), Amman in Jordan (75km), and the south of Lebanon (140km). Searching closer to home, Tinder provided an unpleasant reminder that for those who stay within their West Bank cities, illegal and often hostile Israeli settlers are everywhere. I was horrified and yet fascinated as I swiped my way through hundreds of profiles to see Israeli man after Israeli man, as close as 2 kilometres away, inside Palestine. As an anthropologist looking at everyday life, daily routines, and how people use and understood the ethnically segregated space around them, I was hooked.

While there has been considerable discussion of how we use social media within anthropological circles, in my review of the literature I found that little attention has been paid to Tinder as a tool, whether used personally or professionally.

Tinder and similar location-based apps allow us to see how users present themselves to the world and have remote contact with otherwise inaccessible populations. Of course, such access in a romantic and/or sexual context also raises some important ethical and methodological questions. How can we harness popular social media platforms for research purposes? Can we differentiate between using them both personally and professionally? What are the ethical ramifications of using something like Tinder as a research tool?

Social mapping

If you stay inside Palestinian cities and you have no personal connections with Israelis, the spatiality of the occupation can be hard to understand. There is no longer an area called Palestine that is populated solely by Palestinians. There are very few maps illustrating the demographic breakdowns of the Occupied West Bank, not to mention up to date ones as the illegal Israeli settlements continue to expand. “Area A”[1] is limited to the biggest cities, shrinking and often violated. The spaces between and encroaching into these cities (“Area C”, about 60% of the West Bank) are now populated by approximately 600,000 Jewish settlers, including the ultra-Zionist, the ultra-orthodox, and increasingly the right-wing working classes, all attracted to the settlements’ government subsidisation of housing (for Jewish citizens only). The populations are mixed, but not mixing, and education about either side is detrimental and/or non-existent.

If you stay inside Palestinian cities and you have no personal connections with Israelis, the spatiality of the occupation can be hard to understand. There is no longer an area called Palestine that is populated solely by Palestinians. There are very few maps illustrating the demographic breakdowns of the Occupied West Bank, not to mention up to date ones as the illegal Israeli settlements continue to expand. “Area A”[1] is limited to the biggest cities, shrinking and often violated. The spaces between and encroaching into these cities (“Area C”, about 60% of the West Bank) are now populated by approximately 600,000 Jewish settlers, including the ultra-Zionist, the ultra-orthodox, and increasingly the right-wing working classes, all attracted to the settlements’ government subsidisation of housing (for Jewish citizens only). The populations are mixed, but not mixing, and education about either side is detrimental and/or non-existent.

Some shared Facebook or other social media interests as well as some peace-building initiatives bring people into contact who might not have been otherwise, but Tinder shows you from the privacy of your home exactly which users are around you (again, filtered through personalised options of gender, age range, and distance). For those who didn’t grow up here, watching the settlements arrive and expand, it is very difficult to conceive of the space not always having been the way it is now, nor the extent of the settler presence.

Tinder assisted in my understanding of just how invasive and close Israeli presence has come to one of the last strongholds of Palestinian space since the creation of the Israeli state in 1948.

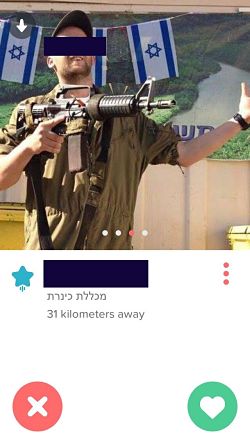

Nationalism

“It’s easy to find someone to talk to but it’s hard to find someone to connect with.”

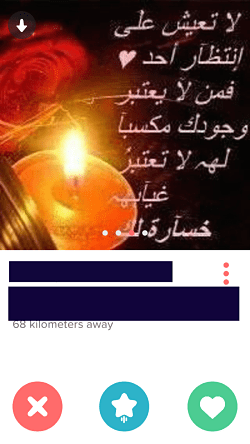

The nationalism I discovered on Tinder was somehow both alarming and fascinating. Most Israeli men I saw had at least one picture of them posing proudly with their guns in army uniform, images from their three years of mandatory national service. Israeli users also often used nationalist memes in lieu of a personal photo or had the Israeli flag washed over their picture. I found far more Israelis than Palestinians[1], and those Palestinian male users generally preferred to use nationalist or romantic memes and quotes, or images of men with keffiiyehs over their faces throwing stones – the archetypal image of the Palestinian resistance actor. Presumably these photos also serve to provide anonymity; Tinder necessitates its users to post pictures on their profile, but it does not discriminate on the content of the picture. Stock images, jokes, and memes are also often used to maintain user privacy. In both conservative Jewish and Muslim cultures, Tinder creates a context where young men and women may be alone together, going against social convention. Therefore its users may prefer to keep themselves anonymous while browsing other users.

Israeli Tinder users appear to concretise a Zionist ambition of recreating Jews as independent and defensive. Israeli mandatory reserve service requires male citizens to be lifelong soldiers, defenders of the Jewish State. The male Israeli body should be strong, muscular, and powerful. The theme of the male body as defender is also present among Palestinian users. Denied a national army permitted to engage in combat with its occupier, Palestinian men are often civilian soldiers, responsible for the protection of their homes and land. However, as the Israeli occupation government criminalises the right of resistance, the Palestinian soldier hides his face behind his keffiyeh or hides his identity entirely behind a selection of romantic quotes and ideas.

It must be acknowledged that because Tinder users are most likely in pursuit of romance and/or sex, the ways in which users communicate with each other may be flirtatious, sexually forward, or presenting a more attractive and accommodating version of themselves. One could say politely that it’s a ‘less than professional’ context. My matches often directed our conversations towards things we had in common or places we could go, paying me compliments, asking when we could meet, and extolling their personal virtues in an attempt to get my phone number and/or meet.

It must be acknowledged that because Tinder users are most likely in pursuit of romance and/or sex, the ways in which users communicate with each other may be flirtatious, sexually forward, or presenting a more attractive and accommodating version of themselves. One could say politely that it’s a ‘less than professional’ context. My matches often directed our conversations towards things we had in common or places we could go, paying me compliments, asking when we could meet, and extolling their personal virtues in an attempt to get my phone number and/or meet.

The way we present ourselves on Tinder is not necessarily the way we may present ourselves in other formats and platforms – for example we may be more flirtatious, try to appear more outgoing, more funny, or otherwise more appealing to the opposite sex. But since this behavioural adjustment may also happen in face-to-face encounters between anthropologists and their interlocutors, does this mean we cannot use it as a form of legitimate empirical data collection? As an example, if I ever confessed my own politics or residence in Palestine to my Israeli matches, they often attempted to ‘convert’ and ‘explain’ to me their side, or quickly label me a terrorist sympathiser. The Palestinder Project[2] documents the average content of such exchanges, and while presented in a comedic fashion, the creators use screenshots of conversations between the two groups to emphasise the miseducation and mistrust among the populations. Tinder conversations in general are marketed as stereotypically brief and light, flirtatious. Here in the West Bank chats between Tinder users can quickly turn into a heated political argument unless directed away from the issues on the ground: the occupation, the Wall, the mobility restrictions, the IOF, my work. In this sense I too was adjusting the way I communicated with Israelis in order to get them to communicate with me.

Cultural knowledge

Tinder is also useful for expanding my knowledge of Israeli culture, as a kind of social gauge, a way to keep in touch with Israelis on my own terms with a relatively anonymous profile. When chatting with Israeli Tinder matches that I chose for both personal and professional reasons, I would tell them I lived in Jerusalem. And as I got to know the city better, I was able to provide more convincing details about where I might live, as well as which details to leave out. If I felt like provoking a political discussion I could even ‘come clean’ about my real work or location. I was even lucky enough to find a few who lived in the settlement I planned to conduct further research in. Whenever I did tell settlers I was researching them, they told me either that there was ‘nothing there’ or that they were ‘monkeys.’

Tinder is also useful for expanding my knowledge of Israeli culture, as a kind of social gauge, a way to keep in touch with Israelis on my own terms with a relatively anonymous profile. When chatting with Israeli Tinder matches that I chose for both personal and professional reasons, I would tell them I lived in Jerusalem. And as I got to know the city better, I was able to provide more convincing details about where I might live, as well as which details to leave out. If I felt like provoking a political discussion I could even ‘come clean’ about my real work or location. I was even lucky enough to find a few who lived in the settlement I planned to conduct further research in. Whenever I did tell settlers I was researching them, they told me either that there was ‘nothing there’ or that they were ‘monkeys.’

Upon learning I was a foreigner, most men wanted to know my opinion about the regional political situation. My answer was usually that it was ‘complicated,’ and many responded with the view that ‘Arabs wanted war’ and they were proud to have served in the IOF that violently oppresses them. “Palestine”, for these men, was simply a place referred to as where the “hostile Arabs” live and where they went when serving in the IOF, not a place where foreigners might safely go or where Tinder might happen.

I only ever met up with one match who fulfilled my research criteria, and because I was on the fence about whether it was a research or romantic interaction, I didn’t tell him about my work. It became clear to me during our date that we weren’t a romantic match, and since he still seemed interested in pursuing a romantic path I decided it was unethical to continue to meet with him as a research contact. I explained the situation to him but he expressed a desire to continue to pursue a romantic relationship despite my decision against it. Aside from the fact that he didn’t accept my rejection, I felt uncomfortable trying to build a working relationship with someone who would be waiting for me to ‘change my mind’ about him. Although the situation of unrequited attraction between researchers and interlocutors may well be common, Tinder’s remoteness allowed me to navigate this discomfort in a new and potentially safer way – I never had to use my real name, phone number, or feel rude disappearing afterwards.

Language practice

Tinder is exceptionally useful for keeping up on language skills. While I currently work in Palestine, my two years of Hebrew study have deteriorated – apart from conversational practice on Tinder. As similar Semitic languages, Hebrew and Arabic are two languages that are not to be confused, so this text-based method saved me the embarrassment of mixing up spoken Hebrew and Arabic with the wrong people. Using Tinder, I could have small conversations in Hebrew and keep my vocabulary alive without needing to speak out loud and avoiding confusing vocabulary. It’s not perfect, but it has certainly been useful.

Tinder as a methodological tool

Accessing my research subjects in this remote and limited manner allows me to multi-task, ethnographically, and ‘go over to the other side’ occasionally to check in with my informants on my own terms. If I want, I can pick an Israeli seemingly at random from Tinder, travel the short distance across the Apartheid Wall to West Jerusalem, talk to them, and then return to my own fieldsite where dating is difficult and contact with Israelis is limited, as is even leaving the West Bank for most. Despite maintaining honest relations with my Tinder matches, I feel a twinge of guilt when using data I’ve gleaned from conversations or people I’ve met from Tinder, as if this is somehow not legitimate anthropological knowledge.

Ethically, we must wonder if it is acceptable to meet potential research subjects in a dating or romantic context when you might have no intention of becoming involved with them romantically.

Or alternatively, is it ethically acceptable to meet potential research subjects in a dating or romantic context when you do have the intention of becoming involved with them romantically? I have been, for the most part, honest and open with those I have met regarding my intentions and profession, but this doesn’t necessarily stop people’s feelings from being hurt, or worse. Whatever my intention is in a new conversation with a Tinder match or Tinder interlocutor, I have always informed them that I’m a researcher of Israelis, which I can then position myself as politically neutral or otherwise – this is also a tactic I use outside the realm of Tinder, depending on who I’m talking to. If necessary I can hide the elements of my work that might trigger an argument or the portrayal of myself as a person opposed to Israel. This is achieved by highlighting the less political elements of my work and focusing on Israeli culture, which tends to flatter my (Israeli) Tinder contacts and potentially gain insight into their experiences. These are techniques that anthropologists may also employ in face-to-face interactions. And thus far it has worked, in that my interlocutors on Tinder have been accepting and interested in my work, often offering to meet and tell me about their lives. Establishing the context of research before a date or a romantic interaction where either party is free to reject the company of the other party felt like an interview situation to me, where the premise is similar.

So the question is, how do other people use Tinder and any similar social media/apps for their work? Where do we draw a line with what is and isn’t deemed scientific, objective, anthropological data? What are the anthropological uses for Tinder other than in the investigation of divided populations? These days ethnographic fieldwork is often accompanied by our smartphones, WIFI, Facebook, and the ability to stay in regular contact with our loved ones, colleagues, and new research contacts. Alongside this we have new ways of meeting and staying in touch with our interlocutors, new ways of meeting new people that can come with certain contexts or expectations, which requires us to investigate the ways we collect data and the ramifications behind them. Using romance as a context through which we can explore the cultures that we live in, and in my case, the ones that we don’t, can open otherwise closed doors. Meanwhile the remote quality of smartphone communication gives an added protection of distance and safety for ethnographers unable to move freely between spaces.

Tinder might not be the most perfect way of conducting ethnographic research, but it certainly opens up a new space for safe cultural exploration for ethnographers in difficult locations.

[1] This is discernable from name, language used on profile, and general physiology/use of national symbols in profiles.

[2] A tongue-in-cheek look at several foreigners’ Tinder and Grinder conversations with Israelis while living in the Palestinian West Bank during the 2014 Gaza War.

[1] The Occupied West Bank was divided into Areas A, B, and C after the 1994 Oslo Accords. Area A contains the major Palestinian cities, Area B is designated mixed industrial space, and Area C, which over 60% of the West Bank is designated, is mixed Palestinian and settler space, where Palestinians are forbidden from building new structures.

Interested in more? Don’t miss Anya’s follow-up post.

Featured image (modified) by israeltourism (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

This post was first published on 2 May 2017.

Anya is a PhD candidate currently conducting ethnographic research in Palestine. Her work revolves around issues of the everyday of colonisation. She also works on issues of gender and fieldwork, alternative methodologies and mental self-care.

-

-

-